The Telrad and the Rigel

Quickfinder are two of the most popular "unit" (non-magnifying) finders

in amateur astronomy today, followed closely by the red-dot or BB-gun

finder. All three use the same basic technology: they focus a reticle

image at infinity so it will stay put when you move your head from side

to side, and you look through the reticle glass at your target.

There's the rub. There's always a piece of glass between your eye and

the target, dimming the target's light. There's a glowing reticle on the

glass, too, further diminishing your ability to see faint targets.

Telrads and Rigels let you blink the reticle on and off so you can see

your target, then the reticle, then your target...but you've still got

that glass in the way. Wouldn't it be cool if there was some way to let

the light from your target fall straight into your eye without going

through anything inbetween, yet still be able to see your reticle at

whatever intensity you wanted?

Indeed it would be cool. And the gadget that does this is

called the split-pupil finder. Particularly the "glow" variety of

split-pupil finder. It's one of the simplest, most elegant finders

possible, second only to a peep sight in simplicity. It's quite possibly

the lightest finder you'll ever use, too. It consists of only three

elements: a lens, a glowing arrow, and a stick to hold the two apart at

the correct distance. Here's a photo of me looking through one.

I belong to a group

of amateur telescope makers called the Scopewerks, started by David

Davis of Toledo, Oregon. Two of our members, Chuck Lott and Craig

Daniels, like to build finders. Chuck has made hundreds of different

types, including the infamous 35mm finder

described here.

I belong to a group

of amateur telescope makers called the Scopewerks, started by David

Davis of Toledo, Oregon. Two of our members, Chuck Lott and Craig

Daniels, like to build finders. Chuck has made hundreds of different

types, including the infamous 35mm finder

described here.  Many of Chuck's designs (click

here for more) use the "split pupil" effect. It's called that

because you're using one eye to see two things at once. The upper half

of your pupil lets in light from your target, while the lower half of

your pupil lets in light from an arrow that points at your target. Both

images are combined on your retina to create a superimposed image of

your target and the pointer.

Many of Chuck's designs (click

here for more) use the "split pupil" effect. It's called that

because you're using one eye to see two things at once. The upper half

of your pupil lets in light from your target, while the lower half of

your pupil lets in light from an arrow that points at your target. Both

images are combined on your retina to create a superimposed image of

your target and the pointer.

That sounds cool enough, but it gets better: When you look through the lens, the arrow is focused at infinity, which means it stays put when you move your head around. (At least until its image slides out of the view of the lens.) And when you move your eye up to the top edge of the lens...magic happens. The arrow begins to slowly fade out, top first, and you begin to see what lies beyond it. You're seeing that directly over the lens, with nothing but air between you and your target. Yet you've got a ghostly arrow pointing right at it. Move your head down a little bit and the arrow grows more distinct. Move it upward, and the target beyond grows more distinct. If that's not the coolest finder concept in the world, I don't know what is.

Chuck likes to make the pointers out of LEDs with variable brightness

and various shaped reticles in front of them. Craig got to wondering if

he could substitute a strip of glow-in-the-dark tape for the LED,

eliminating the need for a battery, LED, wires, dimmer, etc. He

had a bunch of old plastic lenses lying around, so he cut the top off

one and mounted it on one end of a length of wood, with the glow-in-the

dark arrow stuck to a block on the other side.

Voila! Same split-pupil effect, with just about the simplest materials

imaginable.

Here's a longer version that I made.

Here's what it looks like if you're looking down the

body of it with your eye well above the lens. If you're looking at your

target (the distant tree top), then the arrow is out of focus because

it's too close to your eye. It will also move from side to side as you

move your head sideways. (That's called parallax.)

When you look through the lens at the arrow, the arrow is in

focus and stays put when you move your head around. If you move your eye

up to the top of the lens, the arrow starts to fade out and your target

appears where the top of the arrow was. You can bob your head up

and down to see one, then the other, or

both simultaneously when you hit the sweet spot.

This works best when your eye is close to the lens, and at

night when your pupil is dilated. Why does it work best with a dilated

pupil? Because a dilated pupil leaves more room for the light to pass

over the lens into your eye as well as through the lens into your eye.

How to use the finder

You use this finder to locate objects in the sky the same way

you use any finder: look through the lens at the arrow, then swing the

telescope around until the arrow points at your target. When you get

close, start using the split-pupil effect to refine your aim until the

target is resting right on the top of the blunt arrow.

Why the blunt arrow? Wouldn't it make more sense to make

the arrow sharp? You'd think so, but no. A sharp arrow disappears

near the tip from simple lack of brightness rather than from the split

pupil effect. A blunt arrow only fades out when you want it to, and it

gives you a distinct "landing platform" for your target to rest on, yet

it's still very easy to center the object in the middle of that blunt

platform. Think of it like a gun sight. The sight is quite wide so you

can see it easily, and you rest the target in the middle of the sight.

Why not use both eyes, one for the arrow and the other one for

your target? That way you wouldn't have to bob your head up and

down to get the split-pupil effect. You'd have both the arrow and the

target in view simultaneously, letting your brain do the integration the

way it does naturally.

Ah, the brain. There's the rub. It has evolved to merge two

very similar images together and to provide you with a great deal of

information about objects' range and motion by interpreting the minute

differences between the two images. You don't notice it, but your eyes

twitch back and forth dozens of times per second (called "saccadic

motion") so your brain can refresh the images it gets off the retinae.

If you look at two completely different things, one with each eye, your

eyes twitch around with this natural saccadic motion, and they don't

necessarily settle down to point in the same direction. In fact, without

the same object to lock onto with both eyes, most people's eyes will

drift several degrees away from each other, either cross-eyed or

wall-eyed. If that happens while you're trying to find an object with

this type of finder, you could find yourself pointing several degrees

away from your intended target, even though your brain insists that the

arrow is right over the target.

So: use one eye.

How do you build a split-pupil finder?

Pretty simple. Find yourself a lens with a focal length that's

somewhere around 4-8 inches. Any focal length will do, but really short

focal lengths will make for a scrunched-up, hard-to-align finder, while

really long ones will make for a big, clumsy stick. Put the lens at one

end of the stick and your arrow at the other end, at the focal point of

the lens. You can find that point really easy by using the lens to focus

sunlight on a card taped to the end of a ruler. Your lens will be

resting right over its focal length on the ruler. Careful not to set the

card on fire! (Don't use a lamp or a flashlight for this; your focal

point will be way off. You need a light source at a near-infinite

distance to make this work.)

The body of the finder can be attached to the scope in any way you like that lets you adjust its aim. I use a dowel with a piece of tin (think soup can lid) wrapped around it and screwed to the side of the finder body. I tighten the screw just enough to be snug but still let me twist the finder from side to side and tilt it up and down. I stick the other end of the dowel into a dovetail block so the finder will fit into a standard dovetail mount, but you can mount it any way you like.

That's it. That simple! The photo to the right shows the complete package.

Okay, more detail and theory of operation:

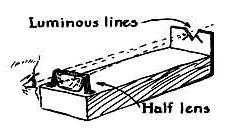

You can see in the photos above that I cut the top third or so off the lens. Why do that? A couple of reasons. A flat top surface lets you slide your head from side to side while aiming the telescope and your arrow slides along with it, uniformly visible the entire way. With a rounded top, the arrow fades out due to the curvature of the lens, so you have to move your head in a curve if you want your arrow to stay equally visible. And the edge of a lens is typically the worst spot, optically, especially with cheap lenses, so cutting off the edge lets you work with the better part of the lens. If you're using a glass lens, it's probably not worth the trouble to cut it (or grind it) down, but if you're using a plastic lens, it probably is.Why not cut the lens in half and get two finders out of it? Good question. To answer it, we need to understand what happens to the arrow when you look at it through a lens. Look at the diagram below. The focal point is out there in front of the center of the lens, but the light rays coming from the lens to your eye are parallel. That means no matter what part of a lens you look through, an object at the focal point (the arrow) looks like it's straight out in front of that part of the lens. You can move your head way off to the side and it looks like the arrow moves with your eye until it moves completely outside the lens. Go ahead and play with a lens and demonstrate this to yourself.

So think about how this works in practice. If you're looking through half a lens at an arrow placed at the lens's focal point, you'll see it in focus and in its real position in space. Raise your head and the arrow will appear over the top of the half-lens, but blurry now because your eye is still focused on infinity. (First scenario in the diagram below.) So far, so good; that's intuitive and exactly what you'd expect. But think about it for a minute: The arrow doesn't fade out when you raise your head; it just goes from being in focus to being blurry. And it blocks your target.

Now look at what happens if you use the top half of the lens (or a whole lens). This is the middle scenario in the diagram below. If you look through the lens at the arrow, it looks fine until you raise your head far enough for the arrow to slide upward out of the lens. But the arrow doesn't appear out there in space, blurry or otherwise! It just fades away (the split pupil effect). You have to raise your head a long ways (the radius of the lens) to see the actual arrow. That's because the arrow is at the lens's focal point, remember? This works fine for a finder. The only downside is that your finder body tilts quite a bit away from straight on. Why does it do that? Because the tip of the arrow is even with the center of the lens. If you build your finder this way, you should mount the lens upright, not tilted like I've shown it in the drawing below. That will give you less distortion from looking through a tilted lens.

The third scenario below, in which you cut off the top third or so of the lens, represents a good compromise between the two extremes above. You get a nice split-pupil effect, the arrow is far enough below the edge of the lens that it doesn't get in the way of your target, and if you make the arrow only as high as the center of the lens, the finder doesn't have to tilt at all. Plus you get more lens area in which to find your arrow when you're looking for it in the dark. But like I said above, it's only worth doing if your lens is easy to cut or grind down. Otherwise just use the entire lens. If you make your arrow only half as high as the lens, you won't have any tilt to the finder body with a full lens, either.

That's pretty much the finder. Build yourself one! Have fun. Play.

This idea isn't new

with me. I got it from Craig Daniels, who got it from Chuck Lott, who

got it from who knows where. There's a mention of the idea in the

"Amateur Scientist" column in the November 1952

This idea isn't new

with me. I got it from Craig Daniels, who got it from Chuck Lott, who

got it from who knows where. There's a mention of the idea in the

"Amateur Scientist" column in the November 1952